PORTRAIT BÄR

MERKMALE

BRAUNBÄR (URSUS ARCTOS)

- Aussehen: Kräftiger, stämmiger Körperbau mit hervorstehendem Schulterhöcker, kurzer Schwanz. Massiver Kopf mit runden Ohren, kleinen Augen und länglicher Schnauze. Fell meist braun mit dunkleren Beinen und Rücken.

- Grösse: Kopfrumpflänge 140–200 cm, Schulterhöhe 70–110 cm. Männchen grösser als Weibchen.

- Gewicht: Männchen 150–280 kg, Weibchen rund 50% leichter.

- Lebenserwartung: bis zu 21 Jahren in freier Wildbahn.

STATUS UND GEFÄHRDUNG

GESETZLICHER STATUS:

- Jagdgesetz, JSG (SR 922.0): geschützt

- Jagdverordnung, JSV (SR 922.01): regelt die Ausnahmen (siehe Vollzugshilfe: Konzept Bär Schweiz)

- Berner Konvention: Anhang II (streng geschützte Tierart)

- EU Habitat Direktiven: Anhänge II (Schutzgebiete zur Erhaltung dieser Art ausweisen) und IV (streng geschützt)

- Washingtoner Artenschutzabkommen, CITES (FR, EN): Appendix II

- Schutz Status CH: ausgestorben (Regionally Extinct); Art mit hoher nationaler Priorität

ROTE LISTE GEFÄHRDETER ARTEN:

In der Schweiz gilt der Braunbär trotz sporadischem Vorkommen weiterhin als ausgestorben, mangels Reproduktion. Aber auch die alpine Gesamtpopulation ist gefährdet durch ihre Kleinheit und langfristig in dieser Form nicht überlebensfähig. Von den 34 bekannten Todesfällen in der Alpenpopulation von 2003–2019 waren fast die Hälfte vom Menschen verursacht, entweder durch Verkehrskollisionen, illegale Tötungen oder legale Tötungen. Zu letzteren gehören auch die zwei Bären, die in der Schweiz als Risikobären eingeschätzt und geschossen wurden.

RAUM- UND SOZIALSTRUKTUR

Braunbären sind sehr anpassungsfähig. Sie nutzen z.B. Wälder, Steppen, karge Gebirgslandschaften oder auch die arktische Tundra. Die heutigen Braunbären Vorkommen sind stark an grossräumig bewaldete, vom Menschen eher dünn besiedelte und meist gebirgige Gebiete gebunden. Eine entscheidende Voraussetzung ist ein reiches Nahrungsangebot. Ebenso wichtig ist aber auch die Möglichkeit, dem Menschen jederzeit ausweichen und sich vor ihm verstecken zu können. Schliesslich braucht der Braunbär möglichst unzugängliche Orte für die Winterruhe: Bei der geringsten Störung wird er wach und verlässt unter Umständen das Winterlager, was besonders bei Bärinnen mit Jungen fatal sein kann: Es kommt vor, dass diese dann die Jungtiere verlassen.

Braunbären leben als Einzelgänger. Die Grösse ihrer Streifgebiete hängt hauptsächlich vom Nahrungsangebot ab. Die erhobenen Werte bei Männchen reichen von 130 km² in Kroatien bis 1’600 km² in Skandinavien. Die Streifgebiete der Bärinnen sind kleiner: Sie liegen bei 60 km² in Kroatien bis 225 km² in Skandinavien. Im Gegensatz zu Luchs und Wolf sind Braunbären nicht territorial: Sie dulden Artgenossen des gleichen Geschlechts in ihrem Lebensraum, denn als vorwiegend vegetarisch lebende Tiere beanspruchen sie kein eigenes Jagdrevier. Bei saisonal hohem Nahrungsangebot können sie vorübergehend gar recht eng beieinander leben. Bekanntes Beispiel hierfür sind die Versammlungen fischender Kodiakbären zur Zeit der Laichwanderung der Lachse in Nordamerika.

FORTPFLANZUNG

Die Paarungszeit, in der Fachsprache ‚Bärzeit‘ genannt, fällt in die Monate Mai bis Juli. Während dieser Zeit kann es zwischen den Männchen zu Kämpfen kommen. Bär und Bärin paaren sich in der Regel mit mehreren Partnern. Die durchschnittlich zwei Jungen eines Wurfs können verschiedene Väter haben. Bald nach der Befruchtung tritt bei den Embryonen ein Entwicklungsstopp ein. Diese Keimruhe dauert bis Ende November, Anfang Dezember. Die eigentliche Tragzeit fällt in die Winterruhe der Bärin und dauert ungefähr 2 Monate. Zwischen Januar und Februar werden im Winterlager zwei bis drei grau-behaarte, blinde Junge geboren. Die Neugeborenen wiegen bloss 200-300 g und sind ausgesprochene Nesthocker. Die Bärin, die während der Winterruhe keine Nahrung zu sich nimmt, versorgt die Jungen mit nahrhafter Milch, so dass diese im April bis Mai die Höhle bereits mit einem Gewicht von 5-6 kg verlassen. Schon bald folgen sie der Mutter auf ausgedehnte Wanderungen. Sie bleiben 1 ½ bis 2 ½ Jahre bei ihr und lernen aktiv von ihr. Eine Bärin kann somit höchstens alle zwei Jahre Junge gebären.

NAHRUNG

Das Nahrungsverhalten der Europäischen Braunbären variiert im Lauf des Jahres stark. Wenn der Bär im Frühling das Winterlager verlässt, muss sein Verdauungsapparat erst wieder an die Nahrungsaufnahme gewöhnt werden. Drei Viertel des Nahrungsbedarfs wird mit pflanzlicher Kost gedeckt, aber auch Aas ist jetzt willkommen. Der sprichwörtliche Bärenhunger erwacht im Spätsommer, wenn es gilt, mit genügend Fettreserven die Winterruhe antreten zu können. Dann fressen Bären vor allem Beeren, Früchte, Nüsse und Honig. Eine wichtige Quelle tierischer Proteine für die Europäischen Braunbären bilden Insekten. Europäische Braunbären jagen opportunistisch und können gelegentlich auch ungeschützte Nutztiere erbeuten. Im Gegensatz dazu jagen und fischen nordamerikanische Bären regelmässig. Faszinierend ist die Winterruhe: In dieser Zeit nehmen die Braunbären weder Nahrung noch Wasser auf und leben allein von den Fettreserven. Weder Kot noch Urin werden ausgeschieden. Der Organismus kann den im Körper entstehenden Harnstoff resorbieren. Bärinnen gebären während dieser Zeit ihre Jungen und versorgen diese mit fettreicher Milch. So ist es nicht verwunderlich, dass Bären während der Winterruhe bis zu 30 % ihres Herbstgewichtes verlieren.

GESCHICHTE IN DER SCHWEIZ

In prähistorischer Zeit besiedelte der Braunbär das ganze Land. Bereits um das Jahr 1500 war er aber nahezu aus dem gesamten, damals schon durchgehend besiedelten und weitgehend entwaldeten Mittelland verschwunden. Zwischen 1800 und 1850 wurden die letzten Braunbären der Nordalpen erlegt. Auch die Jurapopulation verschwand in dieser Zeit. Länger überlebte die Art in den Bündner und Tessiner Alpen. Das Aufkommen moderner Gewehre liess hier die Zahl der Bärenabschüsse nochmals hochschnellen. Zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts war der Braunbär bloss noch im südöstlichen Teil der Schweiz – Unterengadin, Val Müstair und Val dal Spöl – zugegen. 1904 erfolgte der letzte Abschuss auf Schweizer Gebiet, 1923 die letzte Sichtbeobachtung. Schon bald nach der Ausrottung des Braunbären begann die Diskussion über den Wunsch seiner Rückkehr in die Schweiz. Potenziell geeignete Habitate finden sich in den Tessiner und Bündner Alpen in Verbindung mit den waldreichen Alpengebieten Italiens, aus denen der Braunbär einwandern kann. Von 1999 bis 2002 war im Trentino in Italien, etwa 50 km vom Schweizerischen Nationalpark entfernt, ein Projekt zur Wiederansiedlung des Bären in Gang. Mit dem Erfolg dieses Projekts wurde die natürliche Wieder-Einwanderung des Braunbären in der Schweiz immer wahrscheinlicher. Im Juli 2005 konnte der erste Braunbär in der Schweiz seit über 100 Jahren im Unterengadin beobachtet werden. Seither besuchen fast jährlich Bären das Graubünden.

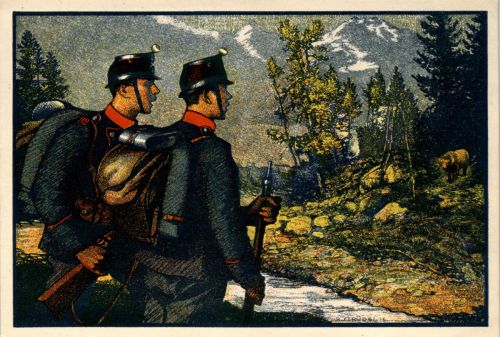

Eine Postkarte (siehe Abbildung) enthält auf der Rückseite eine detaillierte Schilderung der Begegnung:

„Es war anfangs Oktober 1904, als eine Doppelschildwache bei Punt Purif am Spöl im Schweizerischen Nationalpark einen grossen Bären sah. Der Bär kam durch die Geröllhalde westlich Punt Purif herunter und näherte sich dem Posten auf ca. 100 m. Die Soldaten sahen ganz deutlich den grossen Kopf und die grossen Tatzen. Auch am Gang erkannten sie das Tier als Bären. Der eine der Soldaten gab dann zwei Schreckschüsse ab, worauf sich der Bär in riesigen Sprüngen entfernte. Als ich davon hörte, begab ich mich sofort nach Punt Purif und fand die Spur auf dem linken Spölufer im weichen Waldboden. Zernez, 29. Dezember 1914. Lieut. Adank, Bat 92, 2. Komp. – Mitglied des Schweiz. Bund für Naturschutz.“ © Archiv SNP, Zernez

MENSCH UND BÄR

Bären sind scheu und meiden den Menschen, was ihnen dank sehr gutem Geruchs- und Gehörsinn auch meist gelingt. Direkte Begegnungen kommen selten vor, Angriffe nur in Ausnahmefällen. Gefährlich wird es, wenn ein Bär regelmässig in Siedlungsgebieten nach Essbarem sucht. Als ausgesprochener Nahrungsopportunist kann der Bär auch in der Nähe des Menschen geeignetes Futter finden, wenn nicht entsprechende Massnahmen getroffen werden, z.B. bärensichere Abfallbehälter.

Die Vorliebe des Bären für Honig ist legendär. Es kommt immer wieder zu Plünderungen von Bienenstöcken. Durch die Installation von Elektrozäunen lässt sich dies verhindern. Bären erbeuten auch Haustiere. Gefährdet sind dabei besonders unbehirtete Schafe. Werden die Tiere von Hirten und Hunden gehütet und nachts eingepfercht, so kann man das Risiko eines Bärenangriffs minimieren.